Summary

Plants can enhance outdoor air quality, though there is often a misunderstanding about their beneficial impact. Vegetation can trap particulate matter, absorb gases such as SO₂ and O₃, and cool urban heat islands, but these benefits depend on species type, placement, climate, and city-level emission loads. In densely populated cities with high pollution levels, biological filtration alone cannot overcome emissions from vehicles, industries, and waste burning. In fact, larger trees, such as certain eucalyptus species, may exacerbate regional smog by emitting VOCs or by collecting pollutants in their dense canopies. The blog reviews how plants interact with pollution, which pollutants they affect, limitations of plants’ role, and how associated monitoring data is used to assess the effects of green initiatives on air-quality benefit claims.

Can Plants Help Outdoor Air Quality?

We often hear that planting more trees is the answer to polluted cities, but is greenery really a solution, or just a comforting idea? Trees do trap dust, cool hot streets, and absorb gases like NO₂ and O₃, yet cities remain polluted despite large green cover. If plants can “clean the air,” why do smog levels still spike each winter? Why do some leafy boulevards still trap PM₂.₅ at breathing height? And why do certain tree species actually increase ozone formation through VOC emissions? Maybe the question isn’t “Do plants clean the air?” but “How much can they help, and what else is needed?”

Let’s explore plants as part of a solution, not the whole solution.

How Plants Interact With Outdoor Air Pollution

Plants play an active role in altering outdoor air quality. When they come into contact with a pollutant, it is more than just “cleaning the air”: there is deposition, absorption, chemical transformation, and sometimes even release of a given pollutant. Scientifically understanding these mechanisms helps determine what plants can and cannot realistically accomplish for air quality in urban spaces.

1. Surface Deposition of Particulate Matter (PM)

Leaves (especially those with waxy, hairy, or rough surfaces) trap airborne particulate matter. Once deposited, particles may cling until washed off by rain, fall to the ground, or get resuspended back into the air.

Shrubs and hedges are usually more effective than tall trees at trapping roadside dust, as they are closer to the emission height and form surface-level barriers.

2. Absorption of Gaseous Pollutants Through Stomata

In addition to sometimes trapping particulate matter (adsorption), plants absorb certain gaseous pollutants (ozone, SO₂, NO₂, CO₂, and some VOCs) through microscopic openings on leaves (stomata).

Example pathways:

- SO₂ → sulfates → incorporated into amino acids

- O₃ → reactive oxygen species → detoxified via antioxidants

The efficiency depends on:

- Stomatal opening (affected by humidity, heat, drought stress)

- Leaf area index

- Species physiology

3. Chemical Transformation and Phytoremediation

Some pollutants are transformed into less harmful forms either on leaf surfaces or inside plant tissues. Examples:

- NOx reduction via nitrate assimilation

- VOCs degraded into organic acids and sugars

- Ozone neutralized through antioxidant pathways

4. Plants Can Also Produce Pollutants

Not all interactions are positive. Many species emit biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs), such as isoprene and monoterpenes, especially under heat stress. These BVOCs can serve as precursor compounds to pollutants, particularly in the presence of NOx.

5. Microclimate Effects Alter Pollutant Movement

Vegetation alters wind flow, temperature, and humidity. These microclimate changes affect how pollutants disperse:

- Dense tree canopies may reduce airflow in narrow streets, trapping pollutants at breathing height.

- Green belts and shrubs can block and dilute highway emissions if strategically placed.

Which Pollutants Can Plants Help Reduce

Plants affect a variety of pollutants in outdoor air, but their effectiveness depends on plant species, climate, and positioning. However, when weather conditions are dry and windy, some particulates can re-suspend in the air, and pollution can be held at eye-level by dense plant canopy and tree cover in street canyons. These pollutants dissolve into plant internal tissues, where they can be metabolized through chemical reactions, but this is generally limited when stomata close due to heat or drought. Still, many species emit biogenic VOCs like isoprene, which can facilitate ozone and smog formation, so understanding and choosing the right vegetation species is important. In conclusion, vegetation can contribute to cleaner outdoor and indoor air, particularly in low-emission settings, but is best positioned within an overall air pollution reduction strategy rather than as a stand-alone approach.

Why Plants Alone Cannot Solve Outdoor Air Pollution

Although vegetation is an important factor in improving air quality, expecting plants to mitigate polluted outdoor environments is scientifically and practically unrealistic. Absorption capacity of plants decreases under heat stress, drought, and high pollution loads, as stomata close or leaf surfaces become saturated. In these instances, trees transition from active polluters to passive collectors.

Beyond biological limits, urban planning restrictions limit the effectiveness of improving air quality. Selecting poor species that emit biogenic VOCs can increase smog formation. Planning tree canopies incorrectly in narrow streets can disrupt airflow and trap polluted air. Similarly, trees in urban areas, planted far from emission sources, provide little effective benefit, and extensive signature tree plantings require land and space that high-density city spaces and planning guidelines do not always support.

Plants also address pollutants unevenly: for example, they reduce retention and near-surface concentrations of dust, SO₂, and some NO₂, but they do not address black carbon, methane, secondary aerosols, or elevated stack emissions from pollution sources above the tree canopy. Additionally, plants are a useful green infrastructure element, not a replacement for a range of systemic solutions, including emissions control, waste management, cleaner forms of transportation, and, of course, ongoing air quality monitoring to better understand real pollution trends.

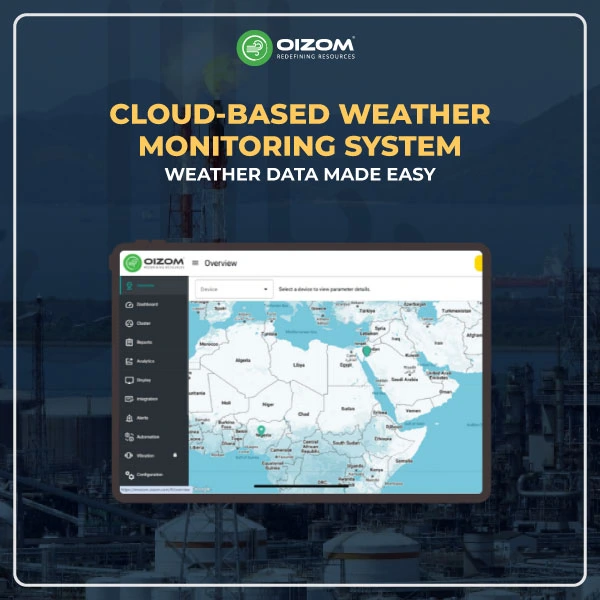

Role of Air Quality Monitoring in Measuring the Impact of Green Initiatives

Green initiatives like urban forests, roadside plantings, EV adoption, or cleaner fuels can’t be evaluated solely on greenery or visual dust reduction. Technologies such as PM sensors, gas analyzers for NO₂, SO₂, and O₃, VOC monitors, and satellite-based aerosol data help determine whether observed improvements are due to vegetation, reduced emissions, or natural seasonal variations. Scalable IoT-based monitoring networks, such as those provided by Oizom, enable cities to track real-world outcomes rather than rely on assumptions.

How Cities Use Plants + Monitoring to Improve Outdoor Air Quality

Cities increasingly combine strategic plantation drives with continuous air quality monitoring to ensure greenery isn’t just aesthetic, but functionally reduces pollution. Rather than blindly planting trees, cities now map emission hotspots, wind flow patterns, and street geometry to determine where vegetation can intercept pollutants and where it may create stagnation.

For example, Singapore integrates vegetation into vertical spaces and highway corridors, but relies on sensor networks to determine whether green corridors actually reduce emissions or merely shift them to adjacent zones. The monitoring mechanism supports adaptive urban planning: plants are added, removed, or repositioned based on real-time pollutant dispersion data.

By pairing greenery with monitoring, cities ensure plantations are placed where they intercept, dilute, or absorb pollutants, rather than creating unintended stagnation.

Practical Scenarios Where Plants Meaningfully Reduce Outdoor Pollution

- Roadside Green Barriers (Traffic Emissions)

Shrubs placed at exhaust height can block PM₂.₅/ PM₁₀ and brake dust near sidewalks, acting as physical filters. - Green Belts Near Industries & Mines

Plantation buffers reduce dust dispersion around quarries and industrial zones. - Vegetation in Schools, Parks & Housing Areas

Creates low-exposure zones in public spaces rather than reducing total emissions. - Highways & Medians (Pollution Path Control)

Corridors disrupt PM travel and reduce long-range dispersion. - Trees for UHI & Ozone Reduction

Shade cools surfaces and indirectly reduces ozone formation.

What Air Quality Monitors Can Reveal That Plants Cannot

Plants interact with pollutants both physically and biochemically, but they don’t measure them. Air quality monitors serve that purpose by measuring pollutants in real time and detecting patterns that vegetation cannot. This measurement enables monitoring to detect invisible pollutants, as plants often filter some pollutants less efficiently, such as ozone spikes responding to sunlight and NOx, or VOCs resulting from fuel evaporation.

Air quality monitors can identify the pollutant source, which vegetation can’t. They can show pollution from traffic peak times and regional weather, emissions from industrial sources in general, or even crop burning, as plants respond to overall pollution. Continuous monitoring will capture temporal variation, such as hourly, weekday/weekend shifts, and seasonal changes, so that interventions can be targeted rather than broad planting.

For example, you could compare PM contamination data before and after planting, between vegetated and non-vegetated corridors, or conduct other recommended studies to quantify how vegetation reduces exposure by intentionally trapping contaminated air in low-ventilation zones. Effectively, any basic monitoring setup could provide data, such as PM counts from electrochemical gas sensors, that vegetation cannot biologically infer. Plants integrated with strategic monitoring can jointly shift environmental efforts from action to measured performance.

Conclusion

Plants undeniably help, whether it’s hedges blocking roadside exhaust, trees cooling down heat islands, or parks creating pockets of cleaner air. Greenery works best when it’s strategic: right species, right placement, right density. A hedge near traffic may reduce exposure; the same tree planted in a narrow lane may trap emissions instead. To truly improve urban air, cities need a layered approach: cleaner fuels, better transport, emission controls, and, yes, smart planting. Monitoring then closes the loop, helping us verify what’s working and what isn’t.

FAQs

Yes, plants can improve outdoor air quality by intercepting particulate matter, absorbing certain gases, and cooling urban environments, but their impact is limited without emission control.

Trees can absorb or capture pollutants only up to their biological and surface-capacity limits, which vary widely by species, climate, and pollution load and are often small compared to total urban emissions.

Yes, vegetation, especially shrubs at exhaust height, can reduce PM₂.₅ and PM₁₀ by trapping particles on leaf surfaces, though captured dust can resuspend, and effects are highly location-dependent.